Investing in Art - The Art of Investing

We create art collections

Art Consulting

Arranging art collections

Cataloguing collections of works of art

Consevation of works of art

From all accounts Kandinsky entered his studio one day and stopped dead in his tracks struck with the beauty of a painting hanging on the wall. He came closer and noticed that the unknown work was his own painting which was put upside down on the wall. This is how abstract art was born, at least according to this anecdote which later led to the treatise entitled “Ueber das Geistige in der Kunst” discussing a spiritual element of art, not excluding however the role of lucky incidents in the artist’s experience. Toutes proportions gardees, people who write about art do also experience lucky events. This is my case for instance.

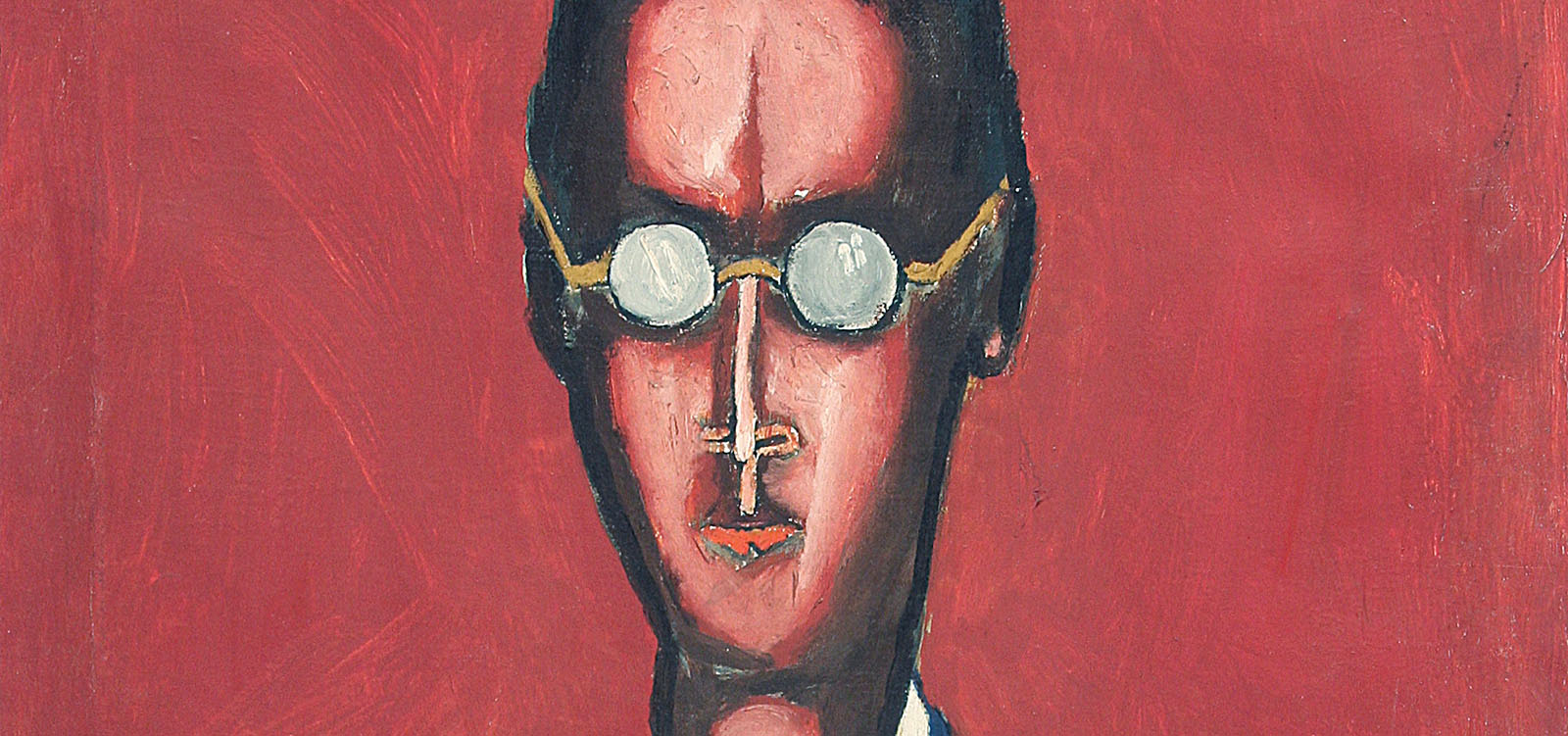

What else can we say about Juliusz Joniak so soon after the publication of the first large album of his paintings, including also an introduction by Zbigniew K.Witek, President of the Society of the Friends of Fine Arts, an analysis by Dr. Józef Grabski and the artist’s own impressions? We could repeat that he is the most outstanding colourist in the present time, which sounds so obvious and banal. We can repeat that his fame is growing, and that he has already gained admiration and respect of even those artistic opponents who have deleted the notion of beauty and good taste from their private glossaries. We can say once again that he is the nicest interlocutor and companion, and that his landscape has been a source of consolation and joy for my soul and eyes for the past two years. We can just as well add that he has entered a new period in his artistic work, the effects of which we can admire at this exhibition and in this album.

Joniak’s art has been developing in phases. He usually chooses a theme, studies its different aspects, enjoys various artistic solutions (painting gives him great joy), studies their different possibilities of expression and improves them. From time to time something new appears in the tissue of his painting, an element which at first seems to have only secondary meaning but which soon starts to develop, to grow, and to gain energy, which emanates from all his canvases, even from his melancholic still lifes.

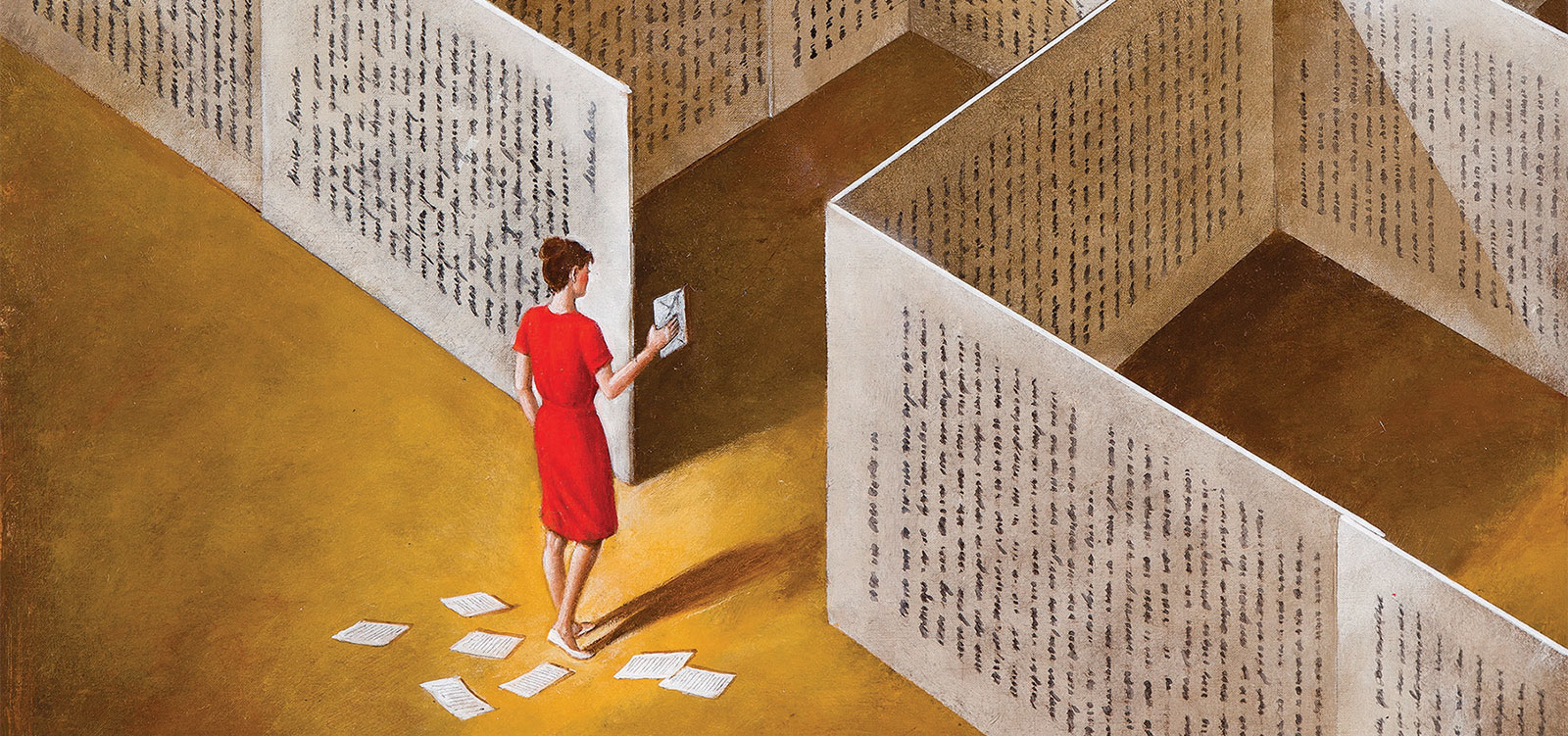

When the task of organizing in some logical framework Joniak’s huge artistic output, comprising over one hundred paintings and a large number of sketches, watercolours and drawings seemed overwhelmingly desperate, a lucky chance let me find a collection of some reproductions prepared for an album. The only problem was that they were black and white. The prints were severe, even ascetic, since they had no luminosity of colouring or the magic effect that only colour tones can produce. We can easily perceive the magic effect of great master’s colour systems and artistic solutions which are beyond verbal analysis. The colouring of Velazquez’s, Monet’s, Cezanne’s, van Gogh’s, Matisse’s works can be recognized and admired at first glance. On the other hand, how could any art critic, even the most confounded one, discuss black and white prints to present the way the artist managed to achieve complete harmony with the use of two contrasting colours?

It would be easy to do it in the case of drawing, which is clear-cut and tangible. It is sometimes called the most faithful means of artistic expression that reflects and represents the artist’s idea. Federigo Zuccaro is an author of the following definition:” drawing is not the matter or the body, but it is the idea, the order, the term, the object of the mind; it is the understanding and the desire…”. These qualities and intentions are clearly visible in the black and white reproductions, namely: the iron discipline of construction, a persistent study of the structure of the world and their transformation into the structure of the painting. One must also mention the consistent order, the rhythm, the balance, the construction of the perspective, the piling of masses, the taming of the energy of slants in order to protect balance from their dynamics and the whole composition from their power so that the beautiful and orderly motion of the cosmos is not turned into its chaos.

I must admit that those old black and white reproductions and coarsely-edited catalogues had their merits, which can be appreciated now through a perverse comparison with excellent and attractive colour reproductions which are so common nowadays. When speaking about black and white reproductions we can also remember that apart from painting Juliusz Joniak also studied graphic art and that he used to emphasize drawing ostentatiously on his canvases. The artist subjected landscape to systems of straight lines which were typical of Mondrian’s precision, and toyed with abstract art, similarly to Kandinsky. His early paintings are strongly geometric, desperately desiring to break free from the confused reality of the world. Nature and the whole visible world with its limitless wealth of forms, colours and possibilities, saturated with care-free fantasy, were reduced to the role of an impulse or a pretext.

However, pure geometry turned out to be too cold, inhuman and devoid of any sexuality whereas Joniak is a sensualist. It proved to have little attraction for someone who is such a wise and thinking being – it was really difficult to be happy about a cube, even if it had the most perfect shape, or to stroke its edges. We can also suspect that geometry was not joyful enough for Joniak since evenits artistic aspect is characterized by asceticism instead of pleasant epicurism. Consequently, soft and organic form, so full of joyful chaos and motion which are synonymous with life and changes, returned in Joniak’s painting. Still, drawing continued to be present in it although it was shifted into the background. It assumed the function of an element controlling and deciding about other components of a painting, including their arrangement and intensity of colours. The number of artistic measures progressively grew smaller and smaller, thanks to which paintings became more perfect. Joniak’s art has developed in the spiral way around an axis denoting the artist’s personality which has the last word to say regarding admissible changes and experiments. Joniak can be included among artists who, as a matter of fact, create one picture all their lives – this is the picture of their internal landscape. Cezanne was one of them. A reproduction of his self-portrait is among different props in Joniak’s studio and has appeared twice in the artist’s still lifes in the past few years. It appears alone or in a symmetrical composition with a cat. Joniak explains that the cat turned out so unexpectedly and out of nowhere that the artist could do nothing else but paint it. Just as well, because a cat can always be useful in the orderly world of art. Too much solemnity and seriousness tire both the author and viewers, do they not? Renoir commented that: ”a painting should be nice and joyful because there are enough of ugly and unpleasant things in the world and there is no need to produce more of them”.

Almost every Joniak’s painting surprises viewers with some artistic paradox. It can be a startling approach to the perspective, an amazing composition of colours, or a combination of abstract forms with obviously trivial objects. His art ogles the audience and smiles to it. Unfortunately, not all viewers are able to see it.

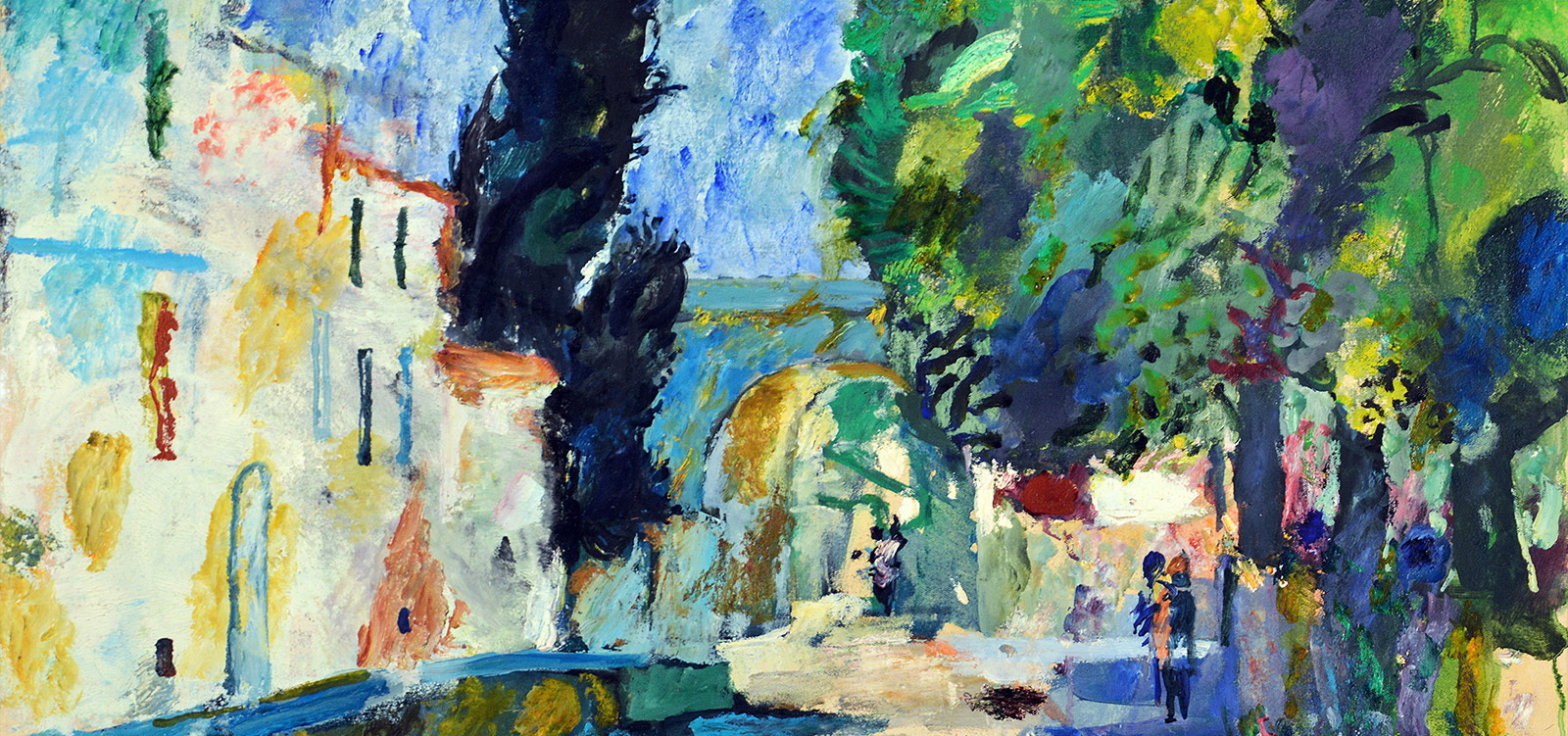

Cezanne painted his “Bathers” nine times and “The Card Players” five times. He repeatedly used some favourite motifs, like for example: a boulevard with chestnut trees in Jas de Boffon, a bay in Marseille, St. Victoire Mount, and other. Juliusz Joniak does likewise. He constructs his still lifes always using the same props – since he cannot always count on the presence of a cat. Every year he goes back to his beloved regions in the south of Europe, to Provance and Spain, to take in the mood of the proverbial joie de vivre and the wonderfully carefree dolce far niente, and paint again his favourite motifs. They are always the same and different at the same time because, according to Zola, landscape is “nature perceived through the artist’s temperament, and temperament is capricious and unstable”. Similarly, consciousness and the hierarchy of values, together with the importance and boldness of decisions are subjected to constant changes. One must remember that Joniak makes only watercolours and sketches during his voyages, which he later develops and transforms when he returns to his studio in Zabierzów. Then he adapts them to “an artistic truth ”which is always more attractive and suggestive than the truth of the reality. These adaptations are more and more decisive and radical. When we see the red dominant of his landscapes from the past floods the whole canvas which glows and blazes whereas straight lines of the stubble field, the yellow trapezium and contours of trees make frames to the composition we come to realize that geometric abstract art has returned in a new and more refined form.

Joniak’s works are more monumental now. Local colour plays a less important role in them. The artist is entering a phase of very personal expressionism which, by the way, has never been strange or unacceptable.

Will the artist ever overstep the limit beyond which “defeated nature lies at the feet of art” like Apollinaire who announced it triumphantly years ago?

It seems unlikely since Joniak appreciates the beauty of nature too much and is too strongly attached to it to want to see it weak and powerless. It is more probable or certain that he will continue to correct it and that he will do it in a more decisive and apodictic way. Expressionism changed the impressionists’ motto “The World and I” into the expressionists’ proud motto “I and the world”, did it not?

Nature can be wrong. True art never is.