Investing in Art - The Art of Investing

We create art collections

Art Consulting

Arranging art collections

Cataloguing collections of works of art

Consevation of works of art

Franciszek Bunsch is a distinguished painter, an unusually astute graphic artist and theoretician of art, and an expert at narration.

This ability to "tell stories", which once used to be common, gradually and slowly disappeared from 20th century art parallel to the departure from the theme and the literary narration of painting that could be expressed in words explaining the artist's idea and intentions. The phenomenon affected all fields of art except graphic art, and particularly the so-called "Cracow school of metal work" which term in the 1960s and 1970s applied to masterly copperplates, etchings and aquatints created under the auspices of the Academy of Fine Arts by such eminent artists as Srzednicki and Wejman and their followers, including Franciszek Bunsch who ranks among the best. The "Cracow school of metalwork" likes to tell stories like any other branch of art which strives to achieve the form with jeweller's precision, to recreate each detail and admire it and its craftsmanship. The rapture of artists who belong to the "school of metalwork" is of somewhat narcissistic nature and relies on pondering upon the perfection of the craftsmanship and its ability to conjure up any forms that the artist may desire. It is the same type of joy which once resulted in an "artistic duel" between two painters, Zeuksis and Parazjos and made young Giotto paint a fly on a still wet surface of the canvas of his teacher Cimabuo when he unsuccessfully tried to get rid of the insect. Illusionary art, the art misleading the eye springs not only from the desire to know and reproduce but from the sense of humour as well because it likes to give joy with the surprise and wonder that it conceals. It is true that nothing is as serious as the laughter of a wise man. Franciszek Bunsch likes to surprise spectators and enjoys astonishing them with some deeply hidden and insignificant details, with a dog's muzzle peeping out from under the table, or an eye staring from the corner of a jester's cap in place of a traditional and common little bell that can be expected at this spot.

Franciszek Bunsch was born in 1926. This was a lucky year for our artists because they were doomed to live hard and turbulent lives and fated to gather experiences, difficult for next generations to comprehend, which in the end moulded their souls and characters. Lucius Seneka, who was not less severely tried, stated: " uninterrupted success will not bear any blow. But he who constantly struggles against his misery owes endurance to his suffering and will not relent to any evil, and even when he falls he will fight on his knees..." Bunsch's generation was particularly privileged in this respect. Obviously if we can include among privileges the pouring disasters known personally to me too because I belong to this generation. This generation is famous for the largest number of artists who created the so-called "museum canon" and whose works are in the collections of all respectable museums.

The war, social realism, the Iron Curtain, separation from the great cultural centres in Western Europe condemned this generation to its individual search for the avant-garde in the art of the interwar period, to flipping through magazines like "The Artists' Voice" (Głos plastykow) and "Arkady", which contained only black and white reproductions, and to begging for prohibited publications in libraries until after 1956 the window to the West and all its novelties was finally opened. The novelties were usually "second hand" because only few artists could afford to travel. In most cases scholarships were not granted to those who deserved them most or needed them to develop themselves as artists. A travel abroad particularly to Paris used to ennoble and promote an artist that is why there were many who craved for it.

In those years everybody missed modernity and everybody accepted it readily even when it was not first-quality. Paradoxically this abnormal or unfortunate circumstances of Polish art was a source of its power and the reason for success. Firstly, our artists had access through the interwar publications and such ambitious magazines as "Przekrój" which propagated the classicists of the avant-garde like Picasso, Leger and Klee, to art which already had truly strong theoretical bases. It was the art which shaped the consciousness of artists in the second and third quarters of the 20th century and has been the foundation of all artistic quests until today. The most influential trends were Cubism, Surrealism and Post-Impressionism as well as some elements of Futurism and Formism. Ephemeral phenomena did not reach Poland. And even when some of them did during the interwar period they were so short-lived that they passed unnoticed.

Cubism was widely admired. Futurism with its formist-like sharp cuts likewise as is visible in folk woodcuts typical of Skoczylas's school characterized also by striking contrasts between profound black and dazzling white. Franciszek Bunsch grew up in such an atmosphere and such were the beginnings of his art. Namely, his was the painting influenced strongly by Post-Impressionism but inclined to geometry and Cubism, tending to organize the surrounding according to logic and searching for proportions, which since ancient times have stood for beauty and perfection. Obviously it was a quest for perfection which is the goal of every artist and for beauty which personifies it and is the ultimate reward. A strong geometric construction is a feature of Franciszek Bunsch's works. It is sometimes more and at times less visible but it is always clear, rational and comprehensible due to its impeccable logic.

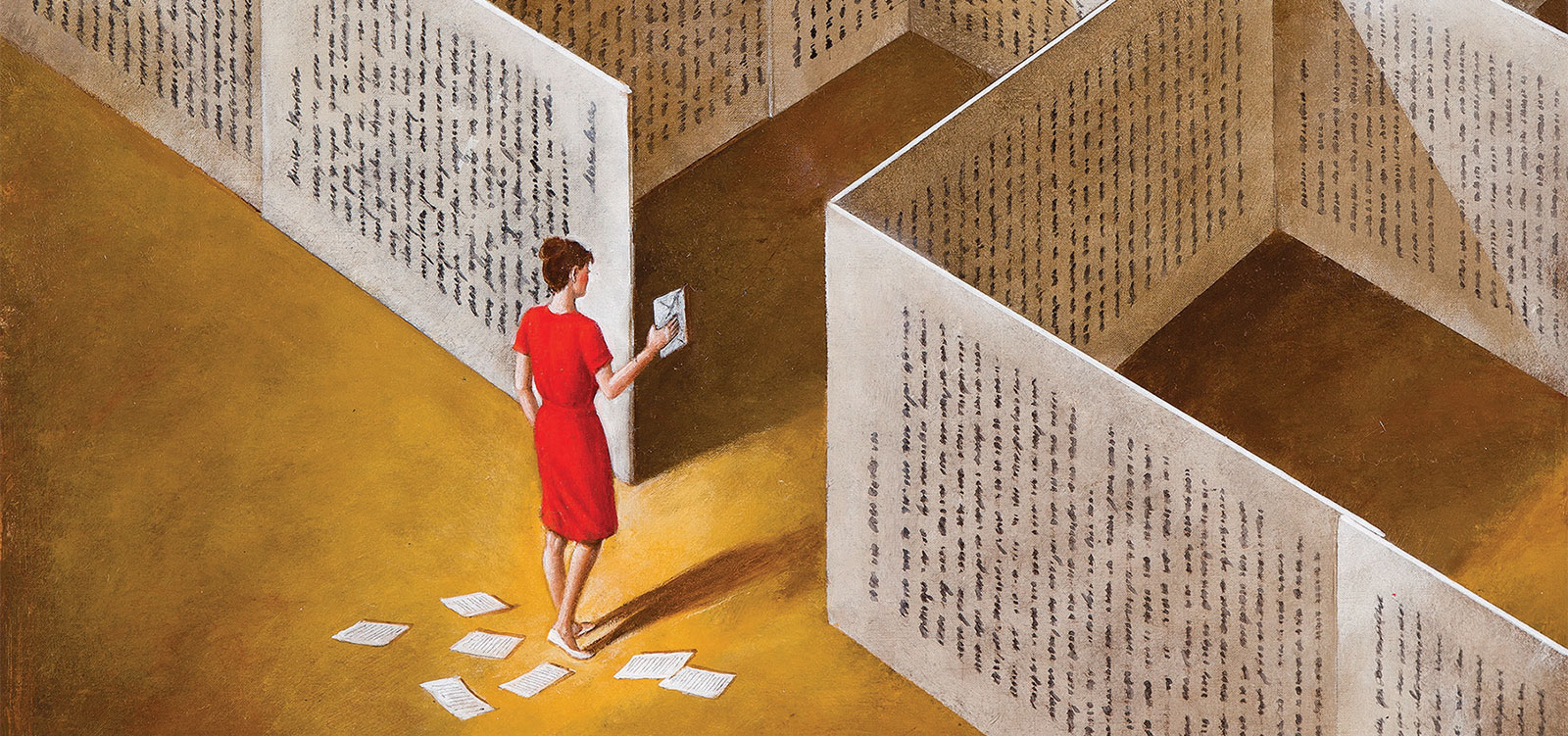

However side by side with logic there appear shapes which on the one hand are realistic but on the other unclear and hard to define. They are disturbing as they seem to conceal some mystery. They sometimes take the form of a drapery or a curtain which hide... What is it that they hide? Perhaps the sacrum, like the draperies hanging behind the backs of rulers in the past, or just on the contrary the profanum of our times and dreams? Good or evil, the future or the past? Or perhaps they conceal the worst - nothingness and emptiness - which the human soul fears most? Franciszek Bunsch was voted a Surrealist because it is this fear and hesitation that construct the fascinating climate of this trend. Also hints which give rise to questions which we are afraid to form and even admit into our consciousness. Is Franciszek Bunsch really a Surrealist and can Surrealism or rather its philosophy of life and the fagon d'etre get involved in the tittle-tattle with its contradiction, that is with Cubism and its derivatives? Yes, of course, this is possible. Even Picasso himself, who is the author and the highest authority on Cubism, cooperated with a Surrealistic magazine "The Minotaur" and designed covers for it. The surreal world is governed by laws identical with the laws binding in the empirical reality. Bunsch, however, does not create clusters of objects nor does he aim at a radical alteration of human consciousness like the true Surrealists did. He does not mean to renounce a pragmatic attitude to the world or submit passively to an unrestrained string of images produced by the brain because such an attitude is inconsistent with an arduous work and thinking process of a graphic artist. The work which requires continuous corrections and long elaborating of the form to perfection forces reflection and criticism in action and in the process of making decisions. Bunsch shares the Surrealists' view that was best expressed in the manifesto written by Breton: "marvellous nature is always beautiful, any marvellous nature is beautiful, only marvellous nature is beautiful". One would like to add that also the work, the discipline of the composition, the charm of labour, and the mastery of forming shapes, and on top of that the quality which is most difficult to achieve, namely the lightness of composition and effortlessness of the execution as if the work came into being by itself, as if black separated spontaneously from white and concentrated in darker of lighter spots, as if the whole composition was still in the process of formation according to the laws of nature. In this case we cannot speak of "the process that the real world undergoes" or of "the merger of dream and reality into the absolute reality that is surreality". In Bunsch's works the trees assume anthropomorphic shapes, hair changes into branches, naked or covered with leaves, the winged rocks resemble men's busts and the organic forms are mixed with geometric ones. Everything may appear and happen. Everything but the chaos because Bunsch's art is subjected to the iron rigour of composition, the order of which is more intricate because it is dynamic, full of vectors crossing diagonally and occasional classical vertical and horizontal planes joined at the right angle. Franciszek Bunsch cannot be categorized univocally. The only unmistaken fact that defines his art is that it is representative of its times and the artist's generation, and that it reflects all the artistic tendencies that fascinated his contemporaries. It is typified by a characteristic passion for creation and for sharing discoveries with others, including the enchantment with Mtoda Polska (Young Poland) with its symbolic romanticism, the logic of Cubism, the art of metaphor which dominated in the 1960s, the "Cracow school of metalwork" and Postimpressionism, characterized by its colouristic culture and admiration for the light playing such an important role in Bunsch's works. In his prints it takes the form of a dramatic chiaroscuro based on a sharp contrast between light and shade which builds depth and a complicated perspective, or a gentle radiance which models soft curves and swellings of objects. However, most frequently light plays a purely emotional role in Bunsch's works. Empty white planes, like in the art of the Far East, become the dominant element of the composition, its most important part, "the contemplative moment" and a space for imagination. It was not a coincidence that Franciszek Bunsch once gave a lecture entitled: "The links between contemporary Polish and traditional Japanese wood engraving" during which he quoted Cze Tao (China c. 1670): "People believe that painting and drawing rely on reproducing forms and similarities. That just is not true! A brush serves to get objects out of chaos". Franciszek Bunsch manages to reveal not only objects but also thoughts and feelings. Sometimes he shows them in direct way using a comprehensible anecdote or an obvious metaphor. More frequently though he gives viewers the freedom of interpretation. In 1975 he wrote: " Should one make accessible to a viewer all the elements that accompanied the process of creation of a particular piece of work? On the one hand this would make comprehension easier for the viewer but on the other would limit his perception. A picture possesses conjectural spheres of which even its author is not fully aware, and which are only hinted at in distant allusions. Do we have the right to stem imagination and the process of developing associations that the artist begins and a viewer should continue? Maybe in this way a viewer will reach his own Arcady? Bunsch is a true member of his generation. He does not try either to impress or dominate or bewilder the viewer. He does not intend to shock the viewer's conscience or horrify him with terrible images. It is clear that the artist does not aspire to the role of the world's conscience and the teacher of morality. What he wishes is to enchant the audience with his imagination and the beauty of his works, their atmosphere and the elegance of artistic effect, the precision of every line and the subtlety of colour. All his works, both wood engravings, prints and paintings arouse admiration and respect like all masterpieces of art and objects executed with absolute artistry.

Many years ago I included Franciszek Bunsch among representatives of the "emotional trend in art because his works, regardless of the degree of deformation or other artistic measures, uphold the same climate, namely the drama. This is because it is the artist's personality and not the motif that are most important in a work of art...". I do not have to change my opinion today. I can only add that his art is more acute, more beautiful and more imaginative than I once thought. First of all its implications leave more space for interpretations. For that very reason Bunsch's works must not be viewed hurriedly, superficially or casually, or at an unseemly time. Just on the contrary, we should study them carefully and attentively so as not to miss any detail or meaning and in order to perceive their poetic climate, discover the relationships between their different components, dissect them into basic elements and put them together again. And then we should stop to muse upon them.