Investing in Art - The Art of Investing

We create art collections

Art Consulting

Arranging art collections

Cataloguing collections of works of art

Consevation of works of art

The so-called art has become stupid, thoughtless, vulgar, assaulting us with shoddy workmanship. Personally, I have nothing against the fact that some faeces fan bought a tin of "Merda d'artista" for 42 thousand pounds in an auction sale, but I don't care about it, it doesn't shock me, it's just boring.

That is why I have stopped going to exhibitions, where the most common display includes left-overs, sperm in a roll or grandma's dirty soap. In a similar fashion, I don't feel like looking at the thousandth black square or at inefficient copies of the works of the ancient masters, which the critics call post-modern art. It is more often with embarrassment than with admiration that I read the acrobatic essays of my former friends, mustering up all their erudition in order to bestow some sense on that jabber which is an offence to human intelligence. Genesis out of Manzoni box!!! Painting is what it has always been: "a flat surface covered with paints in a definite order."

Many a time I have been watching painters visiting museums. They were going from one picture to another, hardly giving them a glimpse, only to stop suddenly in front of the one. They did not care about the author's name, the epoch or the topic, but about the order of paints, which Maurice Denis was writing about, the vista of the paintbrush, the play of colours; in short, the rudimentary features of painting. Of course, the rules were changing. From time to time one could hear voices saying that "the colouring is the matter of imitative skill and practice, not of knowledge and rules", but they were always announcing contempt for workmanship. Fatal contempt, for the history of painting teaches us that a new quality is achieved when one breaks the rules in a conscious way.

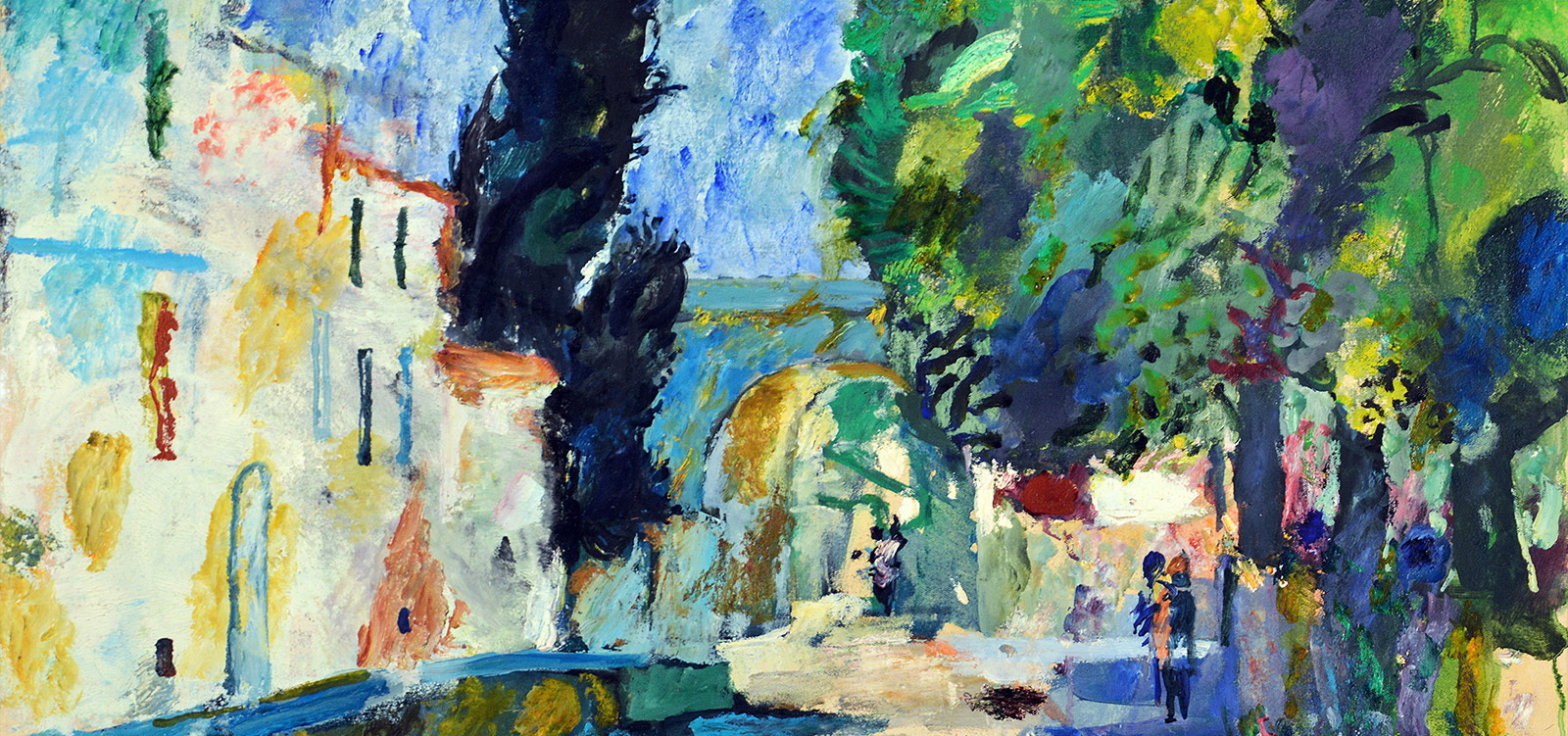

I believe Renata Bonczar when she says that her paintings are created without a deliberate design, because I believe in the creative impulse, categorical imperative and subconsciousness, but I refuse to believe that Renata would paint the way she does were it not for her curiosity about the world and the people, and above all her excellent painting erudition. Thanks to these values she creates original, disquieting, mysterious paintings which move the spectator. Paintings which force the intelligent recipient to asl< questions and which provoke answers. Are there no values where there is no drawing? This was the hypothesis brought forward in 1607 by the President of St. Luke Academy in Rome, a Federigo Zuccaro. By saying that he opened Pandora's box, because the disturbing question has started a chain of fierce arguments flaring up every now and then. Renata's paintings reveal the fact that she's aware of the question, to which she gives no definite answer. It could be postulated that the drawing was more evident in her early paintings (probably under the influence of Jerzy Duda-Gracz, who was her diploma work supervisor), later we can see it clearly in the foreground, as in the picture with two suggestively outlined stones. For some time she seems to be faithful to this principle, but in the paintings from the series "In search of missing towns" the outlines of houses and whole streets remain in the background, whereas the foreground is filled with a fascinating play of colours.

Renata uses colour in a masterly manner. It is colour that organises the space of the paintings, fixes our attention, when arranged diagonally it introduces movement, disturbs us with strong tones.

In "Purple gate", which is more like Christo's curtains, the red is so aggressive that it dominates over the whole composition. It is reflected in the water (which is natural), but it also envelops the horizon in smudges (which is the painter's creation).

"Vermilion red can be compared to the sound of a brass tuba, on occasions also to ear-splitting drum-beat" wrote Kandinsky. Renata grasps his lesson perfectly, she doesn't ignore psychological properties of colours. She knows that yellow is sometimes intolerably obtrusive, blue draws us towards infinity and evokes metaphysical craving. She often uses these colours. She recognises the tranquillity of green, but also its vital potential.

Renata Bonczar's landscapes constitute an imaginary world, sometimes penetrated by remembered elements, such as characteristic Polish willows, villagers' cottages, components of exotic architecture, roadside stones, but also reminiscences of Monet's cathedrals or Bocklin's islands of the dead.

When Renata paints nests with an egg inside, stones or water, she undoubtedly realises subconsciously that they carry the stigmata of symbols, but I don't think that her painting is purposefully symbolic. Of course, an egg is a symbol of life, but in dictionaries of symbols we can find more than twenty distinct, sometimes very dissimilar meanings of that symbol. What about a stone? It is a symbol of the first cause, but also of martyrdom, death and heartlessness. Which of them has been distinguished by the painter? And what about water? It symbolises instability, but in Renata's paintings it is motionless, stock-still like a mirror.

It seems to me that the main function of those nests, stones and water is to let the artist organise the colour scheme of the painting, only indirectly do they speak the language of symbols. It is not through an anecdote or a symbol that Renata's paintings speak to the spectator, they impress us with their indescribable, fascinating expression of form and colour, which is the very essence of painting.

Andrzej Matynia