Investing in Art - The Art of Investing

We create art collections

Art Consulting

Arranging art collections

Cataloguing collections of works of art

Consevation of works of art

Juliusz Joniak painting is as remarkable as it is difficult to describe in words. His paintings belong to the category known to the French as peinture-peinture, that is painting devoid of anecdote, allegory or references to current outside events. Professor Joniak's supply of motifs belongs to the post-Cezanne cannon, thus mostly still life and landscape, more rarely portraiture. In this case, however, the typology becomes unimportant. All of Joniak's pictures spring from observation of reality, the substantiality of the surrounding world, but real subjects are transformed into autonomous structures. Here we are dealing with specific characteristics of the painter's force, with the translation of appearances into paint, with the meeting of forms, colours, and brush strokes whose variety defies any possible schematisation.

The density and sometimes baroque luxuriance of some canvases is curbed only by the artist's innate discipline, which has increased over the years, and his unerring taste. The satisfaction of beholding these pictures comes from a certain astonishment that here we are face to face with something that is a beautiful object but at the same time a phenomenon which mobilises our intellect. It is an individual creation called into existence, but at the same time reveals the unknown in a supposedly well-known world. The moment of astonishment, of surprise, which always occurs when we see a truly creative work of art, appears together with a feeling which is its polar opposite. One could naively express it: "Oh yes, that's exactly how it is; that's the gospel truth."

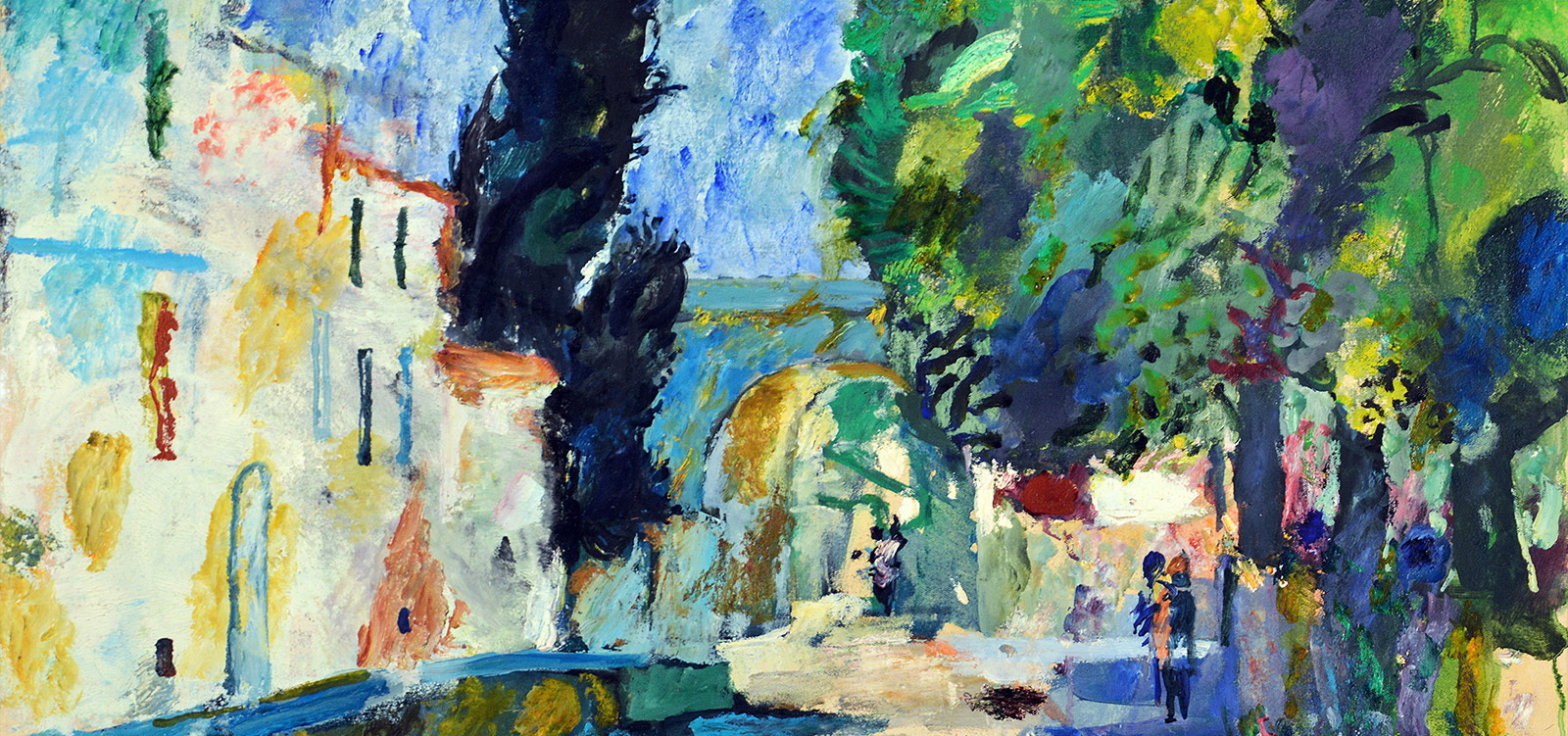

For me, the artist's landscapes of Greece, and especially of Spain, were such a thunderbolt. Capturing this "gospel truth," the quintessence of a given landscape, relies, above all, on the delivery of its colouristic essence. The aura of the Spanish landscapes is delineated by red ochres, browns and blacks oscillating between their poles, small fragments of lime-white, and grey expanses of sky which only on the Spanish plateau has that ashen, dead tone. The artist, when I asked him if he takes some sort of colouristic notes on his travels, answered in the negative. He relies only on memory, in which colour never functions as a separate entity, but as a concrete shade closely bound to the matter of the object. He remembered the colours of Spain as a strap of raw leather, as the precious embossed cordovan, and as a gypsy's little copper kettle.

In the past few years somewhat fewer landscapes have come into being, however the still lifes continue, increasingly refined and mature. Still life beautifully named by the Dutch, has always been Joniak's favourite field for painterly experiments. These experiments have been taking place in the same studio for thirty years, and a certain repertoire of subjects constantly repeats itself. A sapphire-blue glass jug, a dark, timeworn old flagon, a tall, white porcelain pitcher, a net bag containing shrivelled fruits, and a few tapestries, by no means costly, appear in many pictures. This is not anything exceptional, as we may observe this repetition of props already with the Dutch old masters. But their optical realism did not permit transposition. Next, among modern artists the appearance of objects undergoes a kind of reduction, so that they become unrecognisable, and thus in general could not really exist. There are still painters, however, for whom objects have their own existence, but at the same time have different manners of being depending on their context. This serves as an inexhaustible source of solutions. Juliusz Joniak is one of these artists, and the diversity and inventiveness of his decisions, of composition, colour and treatment, cause each canvas to become a wholly distinct phenomenon, though we may after a more lengthy viewing note a few of the same repeated objects.

Juliusz Joniak's remarkable painting has always been too little known here and the present exhibition is the first such large showing of his works in Poland. Professor Joniak exhibits and sells abroad, primarily in Germany, where he has many ardent enthusiasts. This all began when the famous German sculptor, Thomas Duttenhofer, acquired Still Life with a White Vase from an exhibition of Cracovian artists held in Darmstadt in 1985. The owner of an art gallery in Mainz, enchanted by this canvas, travelled especially to Cracow in order to propose a one-man show to the artist. Contact with German galleries developed and stabilised. It is unfortunate that many of Professor Joniak's loveliest works are not found in Polish museums, but abroad.

Maria Rzepińska