Among Józek’s numerous positive characteristics some features are particularly outstanding. These are: a profound and frank optimism and a joy of life. Apart from them it is faith in the immortality of art, its boundless riches and its limited link with life. Józek’s works reflect this attitude.

He was a sportsman and a man of an athletic posture. As a young man he was happy to demonstrate his strength and fitness not only in stadiums or gymnasia. I remember his wrestling with another academic athlete which took place in the study of the President of the TPSP in Pałac Sztuki after one of quite revelry varnishing days there. Wrestling lasted for a while and ended with competitors under the piano, which was happily applauded by guests. We must remember that varnishing days during the so-called “swinging 60s” were not solemn or official occasions. They certainly were not sober.

No wonder that athlete Ząbkowski created a splendid cycle of sports drawing. He rendered motion in synthesis and did it in a wonderful way. What strikes viewers is the ability to show passion and the atmosphere of true sports competition which is well-known to everybody who experienced it. The drawings reflect the joy of victory and the sadness of defeat as well as honour which makes sportsmen fight until the end. The motto of sport, which was amateurish and truly honorary at that time, was: “ If you have fallen – get up and fight”. Józek was true to this motto until the end of his life. He never gave up to his terrible sickness. He always painted believing in Horace’s words, namely non omnis moriar.

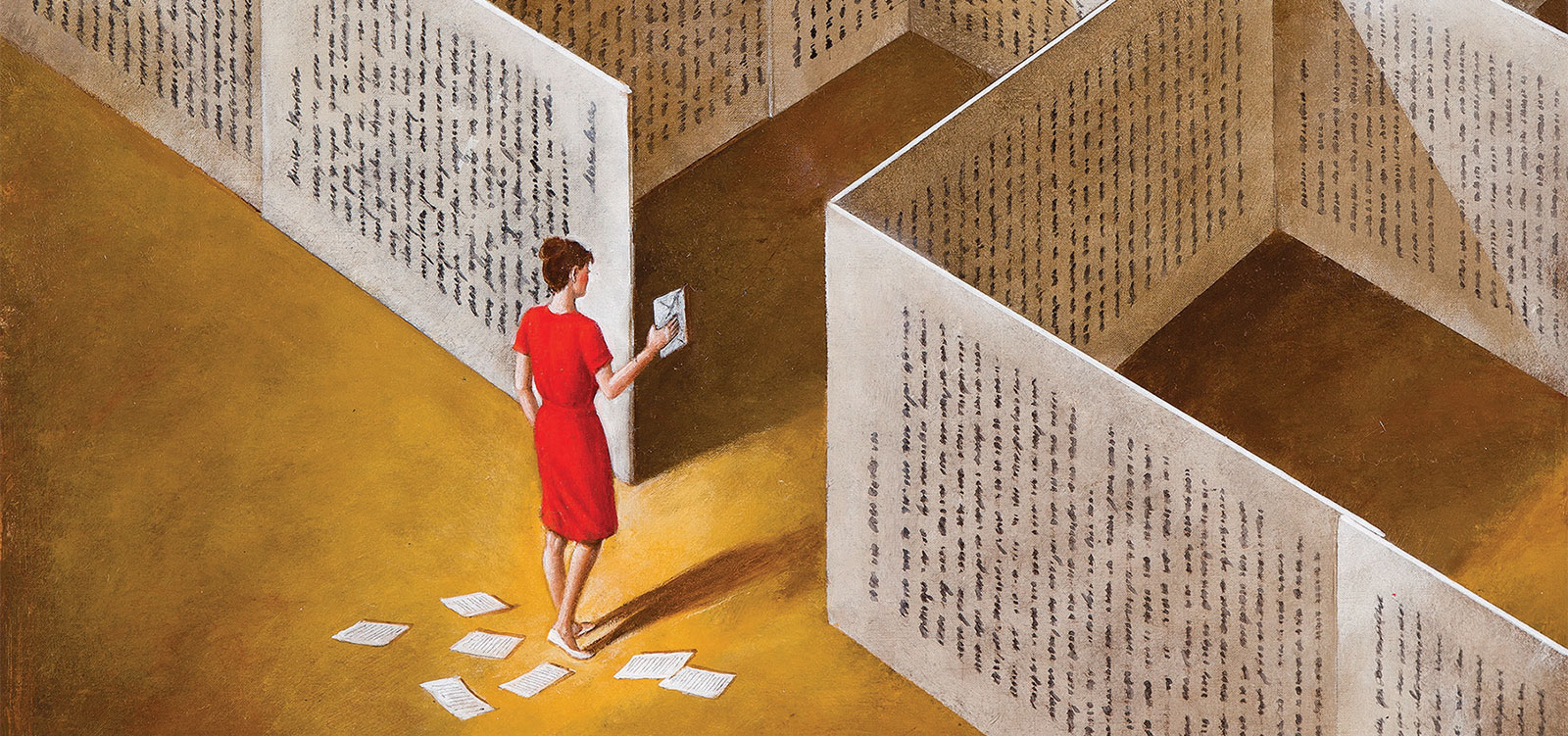

Ząbkowski was a sensualist and he was fully aware of it since he also practiced theory of art. He understood that conscious and controlled sensualism could be a great power. In one of his essays entitled “ Reality and the Form” (Biuletyn Rady Artystycznej ZPAP (Gazette of the Artistic Board of the Association of Polish Artists and Designers) 1/134/1979) he described

the relationship between the artist, reality and creation in the following way:

1. an impact of phenomena occurring in reality on the artist,

2. defining these phenomena by the artist,

3. seeing objects as they are in reality.

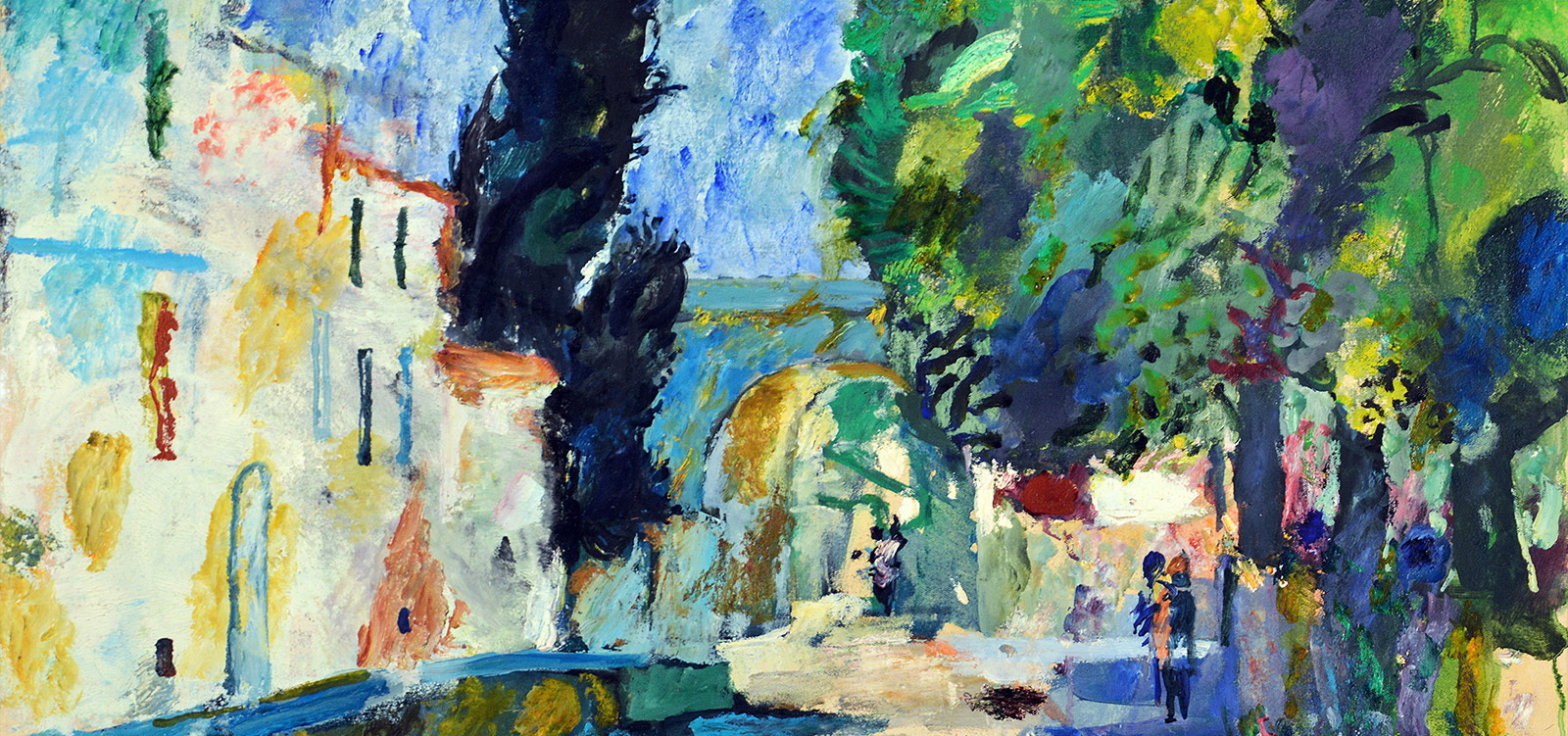

This relationship could be defined with three terms, namely: feeling, understanding and painting. The order of particular phases was important in those years. Emotions and emotional perception of reality came first. This sounded like a programme and ideological declaration or a manifesto, and it stood apart from the avant-garde attempt at scientism, at perceiving and describing the world in the language which was typical of science. Ząbkowski revolted against such an approach to art and its functions. He clearly stated his viewpoint in one of his interviews for a newspaper: “ I respond to stimuli and generally object to a scientific approach to art as I believe it to lead nowhere. Such an approach will not show the artist’s or release viewers’ emotions. Every artist is able to surprise the audience, which is very attractive. But cold and unemotional work rules out the possibility of such surprises ….”. Later he continued: “ First of all I am interested in landscapes. Earlier I used to create compositions with human figures, but now they cannot be found in my works. Recently I had a serious accident. I was hit by a car and I almost died. This experience was not without an influence on my physical condition and on my artistic work. Perhaps it is strange, but now my landscapes seem to be more optimistic, colourful and luminous.”

In Ząbkowski’s later and more mature works the dynamics of drawings with sports motives and the unconstrained freedom of landscapes exploding with feelings became tamed with frames in the literary meaning of the word. He repeated the same motives, window frames, or anything else that was in a rectangular shape on the frames. He himself had a special term for these paintings, describing the way he composed them. One picture was as if composed of two paintings, one on top of the other, in this way expressing two ways of thinking – one of them unrestrained and the other orderly; one object was highly processed and the other was pure abstract art. However, all his paintings were dominated by colour which is synonymous with feeling, sensual attitude to life and joy. Józek always chose colours that were very vivid and expressive. Only later they became dimmer.

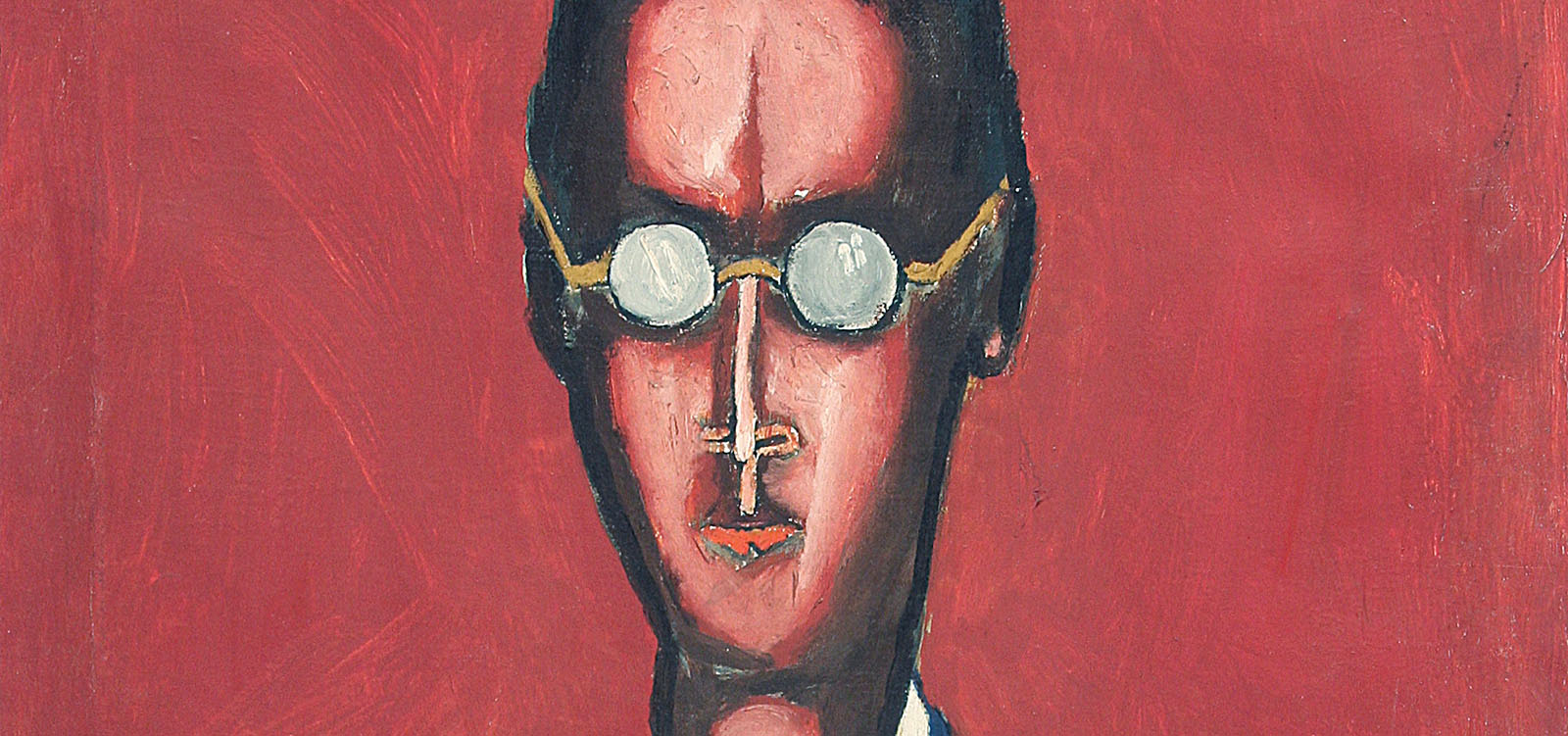

The artist called one of his last cycles “ The World of Objects” and exhibited it in the “Kramy dominikańskie” gallery in February 1987. This “World” is full of mysterious signs, traces of some forgotten script and visions of semi-human faces appearing among shells symbolizing femininity, flowers and plants against the background of stained-glass in the fin de si?cle style. The atmosphere of paintings flooded with the moonlight resembles that of nocturnes which were typical of the art deco period. In one of them you can see a candle which has just been blown. It must have been on for a short moment only. It looks as if it had been lit by mistake and extinguished before its flame had time to glow. There is only a trace of the existence of the flame in the disappearing trail of pale smoke. Its title is “A gate”. Another paining in the cycle is a self-portrait. It shows a face cut with a vertical line emerging from the dark where only nothingness hides. In the foreground there is a skull of a horse shot out of pity by a Polish officer in autumn 1939; the horse had a broken leg and his life was over anyway.

Maria Rzepińska once wrote that Ząbkowski painted his theatrum mundi. However, he first of all painted his theatrum vitae et mortis.

He continued to do it until the last act and the final curtain.

„Cecylia’s painting is not after success but it persistently seeks the truth, the truth of experience and perception of reality and existence. It sometimes has a wonderful power of nature, almost of Demiurgic creation. All these effects are achieved with very simple means and with noble and limited range of colours where paint does not matter and goes beyond the limits of an ordinary raw material ….” wrote Ząbkowski about his wife in the introduction to the catalogue. Harasymowicz also spoke highly of her: “Her landscapes are nervous and violent, one can say quarrelsome – they have nothing in common with the well-known conventional approach to the topic. Cecylia Wodnicka-Ząbkowska is a “cave-painter” and it is very lucky for her. Her paintings are among very few successful attempts at landscape rehabilitation…”. It must be remembered that these words were uttered at the time of the hegemony of abstract art, when any relation with nature was shameful and discrediting.

Maria Rzepińska praised Cecylia’s art: “… There is no ostentatious vehemence [in her painting]. It is a very disciplined painting; the world is concentrated, intimate and devoid of any showiness. These landscapes composed of the simplest expressions are results of true and concentrated effort. They do not show any deliberate overstylisation. These are simply fragments of nature. But also something more than that, resulting from the painter’s deeply penetrating interpretation. Looking at Wodnicka’s landscapes we wonder why these modest canvases typified by dim colours attract attention and are so likeable. This effect is caused by a load of hidden and shy emotions, uttered in a whisper but distinct enough to perceive their profound links with nature…”.

These have been three enthusiastic opinions. Similar and different at the same time. At certain points they are even contradictory or shocking with their broad range of features taken into consideration. According to them Wodnicka-Ząbkowska’s art is a cave-art that is primitive (in the common meaning of this word because the art created by our ancestors 20 thousand years before was extremely refined) but subtle, quiet and sure of its rights but torn by internal doubts, connected with nature and simultaneously creative … The question about what it is like still remains open.

A possible answer to it is that it is typified by all of these qualities at the same time. It is simply rich and free. The artist is endowed by nature with a precious gift. Namely she possesses the freedom of opinion and the ability, or perhaps the internal need, to speak what she feels like or what she believes to be true without paying attention to fashions or artistic trends. This attitude is a source of the artist’s a broad range of forms, climates and concepts. They are all combined with two superior qualities, namely frankness and simplicity of expression. Wodnicka-Ząbkowska avoids decorativeness and coquetry. She never wheedles admiration out of viewers. She paints what she likes and what she finds important and deserving artistic comment.

She is interested in many subjects and motives as well as in many kinds of deformation of reality. It is deformations and transformations which serve artists as means of expression and definition of theirs views on particular phenomena. Cecylia Wodnicka-Ząbkowska employs an extremely broad selection of artistic measures, ranging from solemn monumentalization to joyful and friendly mockery, from monumental landscapes and hieratic sgraffito to strange creatures and birds, from extreme dignity to warm and childish humour and fairy-tales. There are at least two features which link all these contrasting achievements – the first is a warm-hearted approach to every theme and the other is the ability to employ a narrow range of colours dominated by semi-chromatic hues with which the artist is able to achieve a surprising wealth of compositions and tones. Harasymowicz was right in this respect: Wodnicka-Ząbkowska’s landscape do have the quality of “cave-art”. She describes the earth with hues patterned on colours existing in nature, like different shades of clay or soot from the bonfire. Similarly to the authors of the paintings in the cave in Lascaux who had at their disposal only four colours and created the timeless masterpiece, or such ancient masters as Apelles, Aetion, Malthius, and Nikomachus who used the white of Melos, the red of Synopa, the Attika ochre and black called atramenttum. Cecylia Wodnicka-Ząbkowska is a proud continuator of their tradition.

The impression of colourfulness is emphasized by the light, which emanates from canvases, and different tones of colours. The tone is different in each painting but it is always homogenous and compact thanks to the colour ground – the artist does not use white but traditional undercoats instead, particularly Baroque ones. She creates underpaintings in different colours, even in red or dark brown, depending on motives she intends to use or her mood. The artist spends a long time preparing underpaintings, knowing their power of effect and values when they are well-prepared. This observation leads to the discovery of some general truth or a rule, that is what is important in Wodnicka-Ząbkowska’s paintings happens under the “outer skin” of the canvas.

As regards the way of applying paint, she shows preference for the techniques of old masters to hasty painting in the impressionistic “a vista” way. She frequently starts with tempera in order to use oil paints applied “wet” or “dry”. Obviously, the effect of simplicity and unconstraint requires hard work and great skills.

Wodnicka-Ząbkowska is not only a painter. She uses also different techniques. She makes woodcuts, designs and makes mosaics, moulds stucco bas-reliefs and creates unusual sgraffiti, typified by dimmed tones of black and subtle pink hues, thus making them so drastically different from black and white sgraffiti that are most common. She once stated: “A painting must not only be well made from the technical point of view, or have a good composition but first of all it must live its own life.”

This seems to be the most poignant definition of her art – her paintings are really alive.

Marriages between artists are very difficult. Particularly when they are engaged in work in similar fields of art or especially when they work together on the same project. This was exactly the case of Cecylia Wodnicka-Ząbkowska and Józef Ząbkowski. They were a married couple who first studied together in Prof. Marczyński’s and Prof. Taranczewski’s studios at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow and then almost simultaneously prepared their diploma works in 1955 – the year of the “Arsenał” (Arsenal) and the turning-point in our art which at that time began to regain its freedom.

Later their life followed more or less the following pattern: they shared one studio, jointly presented their works at exhibitions and decorated churches together. It seems that it should have sufficed to remove all singular differences between them, to make them merge and consequently, to lose their separate artistic individuality.

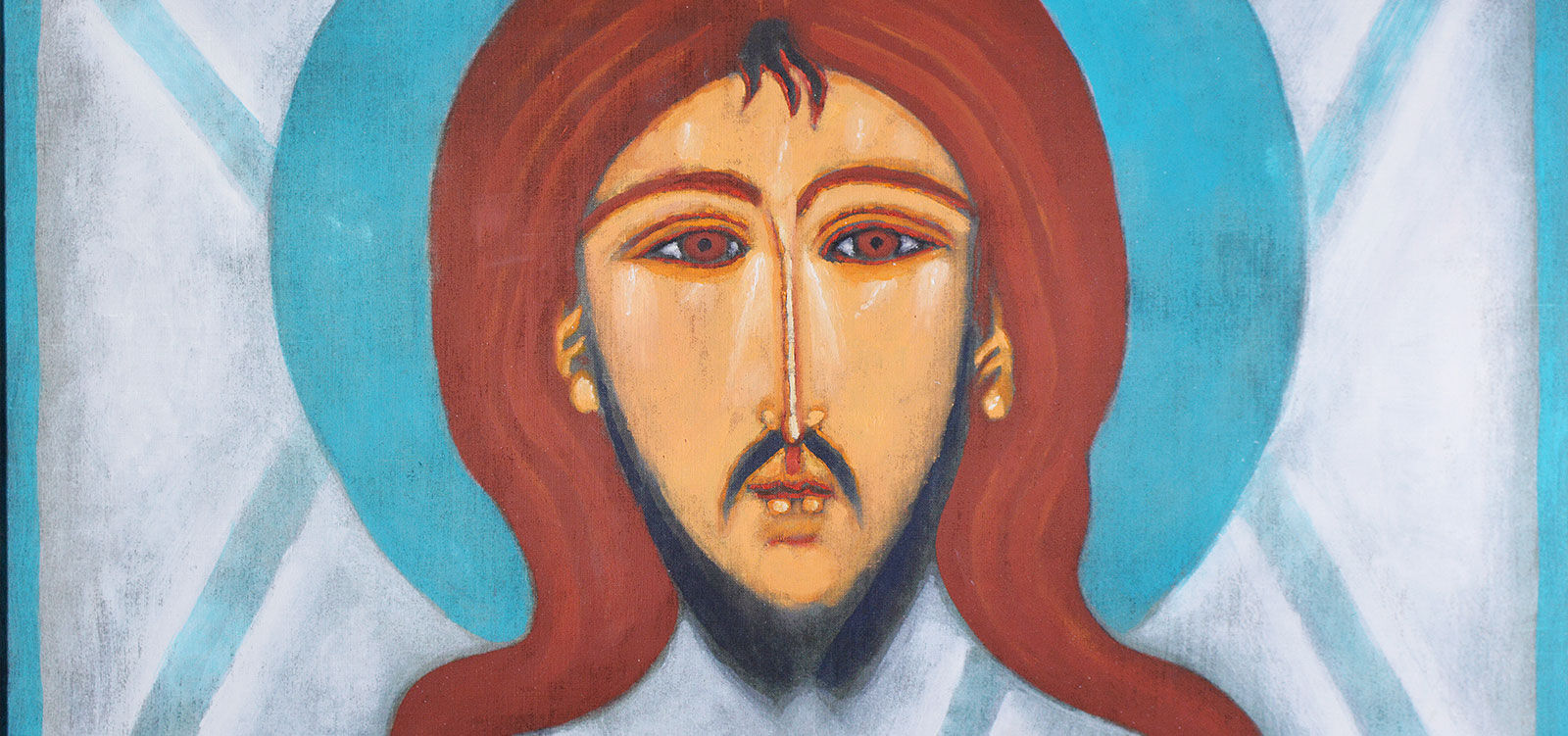

However, the Ząbkowskis managed not no fall into this trap. This was their victory which cannot be overestimated considering the fact that they had so many things in common. They shared things material and abstract, like the understanding of artistic principles and having the same artistic taste. The similarity between them can be defined with the aid of the following anecdote. Many years ago they worked on a project of a stained-glass window for one of those modern concrete churches. It was to be the Annunciation. Like many other religious themes that one is also associated with some representation of a stream of sunrays very much in line with the mysticism of light so advertised and praised by aestheticians and esthetes. Otto Rung, almost our contemporary, arrived at the conclusion that “God is not revealed in light which is white but through colours”. Such a multicoloured stream of light falls from some metaphysical space and illuminates the window with a fairy-like cascade of colours. Since light is an abstract idea which is contrary to commonly accepted in sacred art and expected pictorial accounts of biblical stories after the pattern of the biblia pauperum addressed to the undereducated people in the Middle Ages, the Ząbkowskis decided to cover the abstract stained-glass with a concrete tracery with a graphic representation of Virgin Mary and Archangel Gabriel. The stained-glass window was beautiful, its beauty enhanced by terse lines of the tracery, the black colour of which contrasted sharply with the light. The effect reflects the theory of Mehoffer, the outstanding creator of stained-glass works, who saw how expressive the contrast between the solid elements of the concrete structure and the light was and what strong impression it made on viewers.

Who was the author of the stained-glass window and who of the tracery? Both of them. Whose was the concept and the idea? They created that piece of art together, discussing its details rather than the artistic essence of the matter.

In this little story we particularly clearly notice features that these artists share. These are: firstly, their affiliation to the “art of the light” represented by the impressionism and the post-impressionism at that time (the op-art was in a very early stage of development and so were the light installations), secondly, their liking for the expression, and thirdly, their good taste. At this point the list of the Ząbkowskis’ common features ends and we start to deal with Cecylia Wodnicka-Ząbkowska and Józef Lucjan Ząbkowski. As such they make an interesting theme worthy of a poem by Jerzy Harasymowicz. He devoted one to the two most typical characteristics that unite the couple, i.e. poetry and feeling.